A few years ago, I was living in a dingy apartment, recording dozens of demos for a very dark rock opera. It was a story of rage and despair about everything that seemed wrong with men: war, sex, brutality, insecurity, existential horror. A real “good time”, as they say in disco songs. What I didn’t realize at the time was that while I was having nightly terrors and thoughts of self-immolation, my dirt-cheap, crappy apartment was also doing a fair job of killing me. A few friends commented that they didn’t feel well in my place. I knew that I’d had asbestos fall onto my head when shutting the sticky door, and also had it crumble from the wall when fixing wires in my “studio” (which consisted of a Digi001 and a Mac in my “kitchen”, which was itself merely a small area of the hall with a hot-pot and a mini-fridge). Other events that would have gotten a less self-destructive person out of that place somehow didn’t get me out: carbon monoxide poisoning hospitalized my neighbor in the same building, who was also a musician, and I once when rotating my mattress I found had termite larvae coming out of my mattress. I cut out the colonized portion of the mattress and proceeded with the high life. Good times indeed. But also, what I didn’t know was that in addition to these pleasures I also had toxic mold growing under the floors of in my apartment, which was giving me a nasty cough and also clouding my mental state. I think after a childhood of terror and cowering at home I was so used to being deeply, sickeningly uncomfortable and chronically insomniac that this was what I thought living on my own as an adult was supposed to be like.

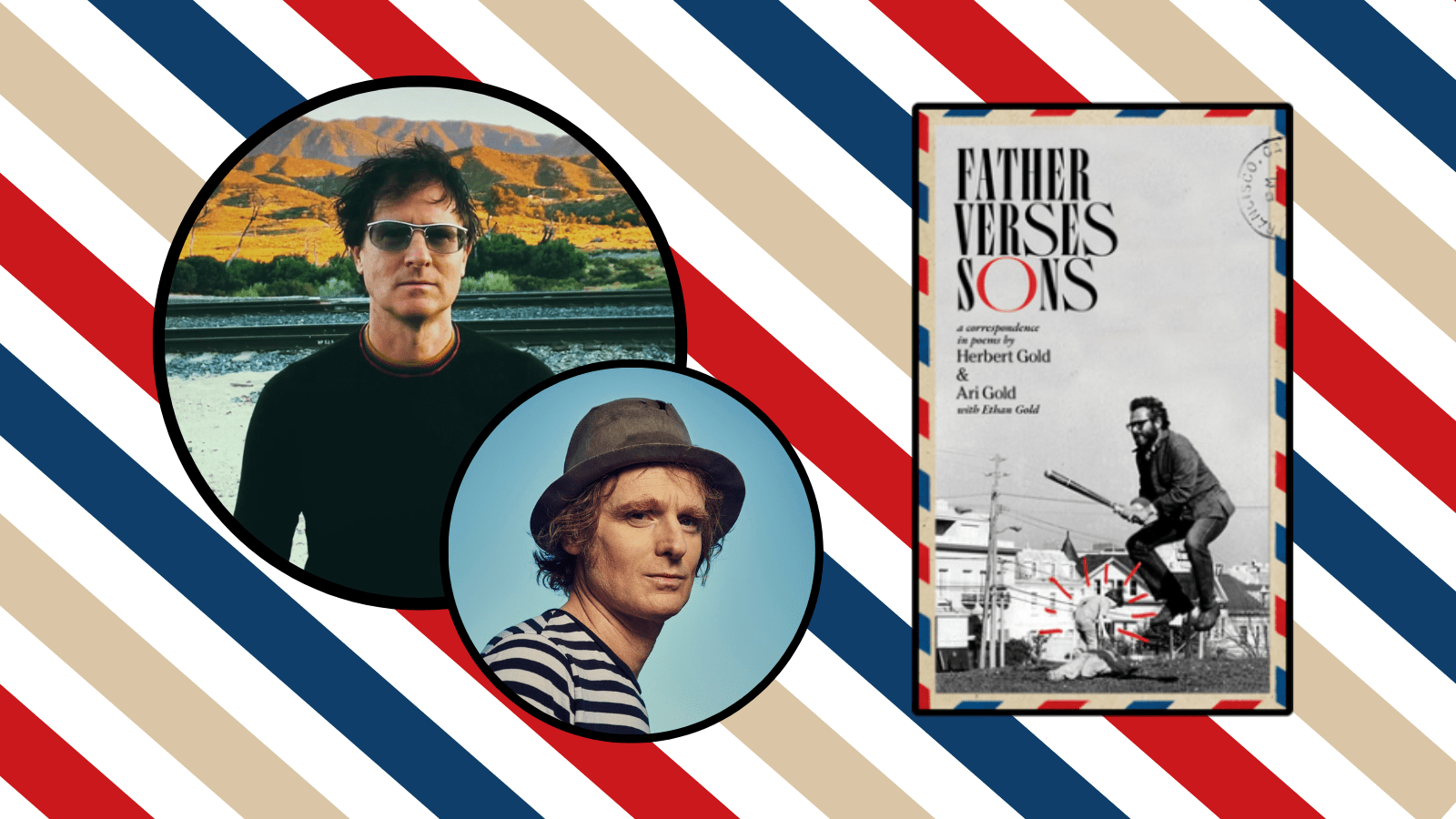

So I proceeded with the demos, while occasionally hosting a show called the Expatriots. This was my way out of the proverbial and likely literal hell-hole: I invited other unknown musicians, friends mostly, to perform songs at various bars and clubs around town. So each night I’d invite three or four musicians to trade songs on stage. My rule was you couldn’t play any set songs, you had to play something inspired by the person who played before you. And preferably tell us how the songs connected. I generally, then as now, found acoustic songwriters so boring, that I had to find a way to bring something that would make good of the only natural advantages of the medium, the intimacy and the storytelling. And it was also the one way I could think of to get myself to play in public, as I was buoyed by the collective strength of the other lost humans I played with. One night a friend of mine brought Elvis Perkins to one of these nights to meet me. Elvis, who I assumed at first was a rockabilly cat because of his name, (certainly not his hairstyle) gave me some songs. I listened to the wandering, sad songs on his demo. But let me go back a bit.

After moving from San Francisco, the city of my childhood, to the city of angles, I’d recorded some of my music and did some short soundtracks, among them a few for my brother, who made a movie called “Helicopter” which was about the death of our mother in a helicopter crash. After three failed marriages and a few step families, an old love affair had rekindled between my mother and Bill Graham, the ‘legendary’ rock impresario behind the Fillmore, Winterland, Day on the Green, the US Festival, and other massive rock venues and concerts. I’d been on stage at and Cheap Trick and Peter Frampton and Black Sabbath (Ronnie James Dio era) concerts as a kid, blowing my ears out and getting zipped around in a side car because of my mom’s rich and famous boyfriend. Now after another marriage and step-family in between they were dating again, my mother living a bit of the glamorous life while Bill was finally with the smart real woman who’d dumped him years before for a cowboy. Anyway, I was just about through, maybe, sorting out the chaos and deep discomfort of my earlier boyhood when the helicopter carrying my mother and Bill from a rock show in the East Bay hit a power line in a storm, and slammed back against a 200-foot unlit tower and exploded.

Cut to a few years later, and I’ve recorded a couple of records for bands in San Francisco, in my mother’s basement. I’d jumped off the college train and become a machine man. I moved to LA to be closer to my brother, who was trying to be a filmmaker and was in the midst of a terrifying breakdown. I started writing my own sarcastic reaction to manhood and rock music that opera thing I called The Rise and Fall of CAP while Ari took more drastic measures. Anyway, in the meantime I recorded more at home and sometimes in a ‘real’ studio, blowing most of the insurance money I’d gotten on my mother’s death. I also got a distaste for the record industry, recording a few things for other artists who took songs and sold them to movies without telling or paying me, etc. The usual stuff everyone loves so much about this business … lambs eaten by sharks … in an amphibious reality … anyway.

Well my brother survived, made “Helicopter”, which I scored and which won a student Academy Award, and I was doing the Expatriots thing, living in the toxic apartment recording 80 demos of the opera, and generally not thriving. Elvis seemed to be in a similar situation, in some ways better off, in some ways more lost than I was. Vague unfocused efforts at recording, general listlessness, obvious sadness and depression. He’d been through something that was more broadly high-profile but also pretty similar to my story. His father was Anthony Perkins, the famous actor. His father had died years before, and then his beautiful, dear mother Berry had been on one of the planes on September 11. So he had had a very public tragedy, several of them, and was, like I was, floating sideways in the putrid wind of grief. But I’d been through it a few years before, and had had a brother who I’d made a movie about the final chapter of our family tragedy with. So I was at that point a half step further along. And I liked his voice and his songs and his spirit, but I could see him and his music just floating sideways in the putrid wind of grief or else getting flattened by one of the various producers nice friends of his famous parents who he was vaguely talking with at the time. I’d had some frustrations with my own earlier attempts to get a sympathetic producer who’d understand what I was wanting to do with music, and through knowing both sides of the lens as it were, I told Elvis what I thought he ought to tell the producers in order to make sure he got something that felt like the full expression of the art he was trying to make. I was advising him for a while on this, over drinks in LA bars and at the shows we started playing together, and at some point in the middle of a show of mine I got a very clear idea in my head of what he should sound like in a recorded form. I jumped off stage to tell him. His songs were poetic but very long either compelling or unfocused, depending on the mood of the listener and the performer. There was something fantastic there but it wasn’t just what he was doing nor was it the pop editing and smoothing out that the producers wanted to do. Inspired by my new notion and by his old demos and his new songs which were now well in my head, I told him how I thought he should sound, how it should be recorded, instrumentation, mood, process. I took inspiration from just three old records, things we both knew and liked, and figured that no-one was doing that anymore. I thought he should to make a pure record, made up of pure performances, something with arrangements and performances that would support a poetic, abstract storytelling style. Instruments and sounds that sound like they’re from another time, a time before electricity. Elvis liked the vision enough to at some point stop asking opinions of me, and just say he wanted me to make his record. So Elvis and my brother helped me move out of the Toxic Apartment, and I agreed to make his record. I think we both thought those naturalistic old records were easy. Well as much as computers can be a bottomless bit, it’s a whole different challenge to produce using absolutely no tricks (or just old tricks), everything the hard way, analog, real performances, music the naked way where it’s either working perfectly or it’s terrible. Those guys in the old days could really play. Those skills seem lost sometimes. But eventually we did it. I built the arrangements that I’d imagined to support his stories, and after a lot of coaxing, pain, and prodding, Elvis shrugged off the haze of lethargy and sadness and gave us searing performances of the songs that were worthy of his beautiful writing.

The world has responded to Ash Wednesday. Elvis had gone back east to school towards the end of the making of the record, where he rejoined with old friends to make a band which could play the songs in their new form. After I mixed the record with our great recordist Dave Ahlert, Elvis took the record back to the east coast and was selling it with his new band Dearland at shows. The blogs started to get it first, in the middle of last year, and the proverbial buzz started, then a label called XL Recordings picked it up, and it’s now just been released to universal acclaim, as you may have heard. Reviews in Rolling Stone, Spin, Filter, Stylus, put it at or above the best records of the indie darlings that we all know and sometimes love. Elvis’s story been framed as a story of loss, and it is that. Ash Wednesday indirectly reflects this country’s great loss, but far more than that it is a totally personal testament to Elvis’ own ride through the darknesses. I hoped to make something timeless, something that is the ideal manifestation of his unique story and spirit, but also something that will sound as good and speak to people as much about grief and beauty in 100 years as it does now.